For Creatures Unseen week, Trevor Hughes, Wildlife Researcher at The Margay Project, on field conservation for nocturnal species...

Tonight, I am struggling and I don’t feel normal at all.

I am 25 meters up a tree in the Panamanian rainforest a few hours walk from base camp. Its 3am, its dark and I am tired from surveying. I have a motion sickness feeling that is not quite right which is most annoying as it’s starting to affect my concentration. I hope it’s not parasitic worms again.

Deciding to call it a night, I turn the red headtorch on and the mystery of my motion sickness is revealed. The tree is swaying not backwards and forwards but in a large figure of 8 pattern. I abseil down, stop 2m off the forest floor, check the landing is clear of any Bushmaster snakes or lurking Jaguars, before continuing to the ground. Packing the harness and optics in the dark, I start the walk back to base camp feeling better knowing that I will be back at base camp for breakfast.

Observing arboreal rainforest mammals at night is not easy and instantly gratifying, it’s difficult, time consuming and frustrating. Traditionally, researchers have ignored arboreal nocturnal mammals for these very reasons. Fortunately, technology to help us is becoming more accessible to conservation sized budgets.

CREA’s Margay Project-Panama, with the support of Welsh Mountain Zoo and Shaldon Wildlife Trust, is currently in the process of a comparative study of some of this available technology. We are using thermal and night vision optics in conjunction with an arboreal and terrestrial camera trap array. Is one more efficient in terms of resources and time or is a combination better? Is it species dependent? How do they perform in the high humidity of the jungle? Questions upon questions.

Using arborist rope access equipment, we were not only able to set the cameras in the canopy but also install small tree seats or tree stands from which to conduct nocturnal observational surveys. The idea was it would then be a simple case of walking to the remote locations and climbing them in the dark, sitting and observing. Whilst partially true, the cold reality we found was different.

Trevor Hughes observing from the tree stand

In our neotropical location the visible scanning zone is foreshortened as the vegetation often closes the direct line of sight to less than 20m to 30m from the observation platform. The field of view through the optics at this distance is relatively small. It requires performing visual sweeps in layers around 270 degrees, stopping, listening, waiting a few minutes then repeating, hour after hour. The brutal fact is that nocturnal surveying in a 3D arboreal environment through a thermal monocular is very tiring.

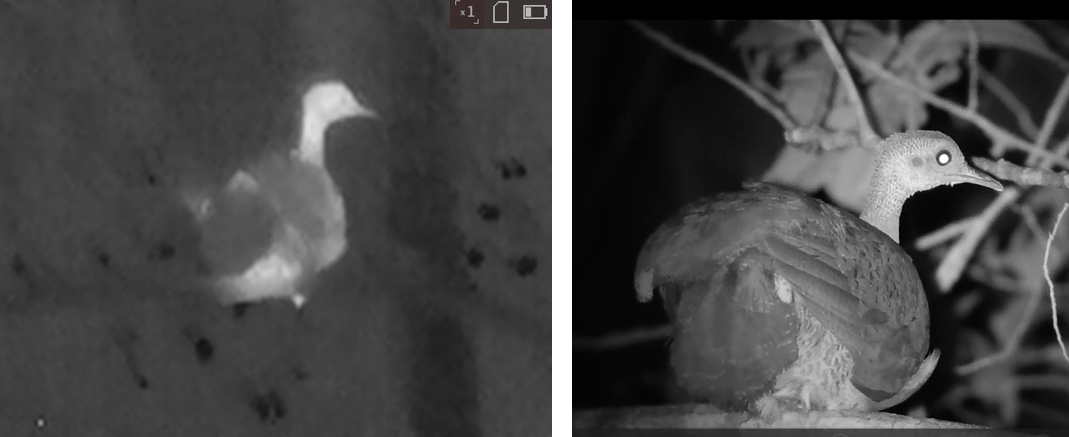

However, when one of the sweeps passes over a mammal the target tends to “jump out” at you. Scan one way nothing, then back and a Tamandua is suddenly visible 20m away. Following porcupines and opossums through the canopy or around a strangler fig is easy, just follow the bright white mammal on the grey black background. Nothing can hide if it’s in direct line of sight and, importantly for us, mammals we observed with thermal technology did not flee or alter their behaviour whilst being watched.

We anticipated that some levels of identification and behavioural observations might not be possible with thermal and so we decided to combine night vision optics with the study. We would locate the mammals with thermal optics and then observe with night vision. In our first season 93% of mammals observed nocturnally were found with thermal optics.

Night vison optics proved much better for full identification but it was noted that some mammals reacted to the infra-red illuminator light, some opossums and sloths altered their behaviour and actively moved away from the survey area as soon as the night vision illuminator was activated.

Images: Great Tinamou taken first with a thermal and second with night-vision highlighting the differences of the two optics for nocturnal work.

Our project was focused on the Margay, observing a semi-arboreal, nocturnal cat in the neotropical forest was never going to be easy. When one considers the difficulty of working at night in such environments, it’s no wonder that many nocturnal, arboreal mammals often have data deficient, little known or understudied in their description.

After the first season it seems the golden ticket does not yet exist. Thermal and night vision equipment was not developed with wildlife researchers needs in mind, however our experience showed they can be very valuable tools. This season, we will be trialling models that should perform better at the shorter distances needed in the rainforest. We hope we can begin to illuminate the lives of these often-ignored ‘creatures unseen’ and that our collective findings can be cascaded on for studying other diverse cryptic mammals such as Andean Porcupine or the iconic Clouded Leopard.

I foresee many more long nights, up trees in the rainforest feeling perfectly normal.

- Trevor Hughes, Wildlife Researcher, The Margay Project

All blogs reflect the views of their author and are not a reflection of BIAZA's positions.

-

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=97e6d151315c515d23f80e6ee9d1d533) BIAZA Blog: How Accreditation is creating change at BIAZA 25th February, 2026After two years of BIAZA Accreditation, the team delivers a look ahead on the programme to support and boost world-class zoos…

BIAZA Blog: How Accreditation is creating change at BIAZA 25th February, 2026After two years of BIAZA Accreditation, the team delivers a look ahead on the programme to support and boost world-class zoos… -

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=a0b01e801771c24b4d7f5c3df4abed98) Twycross Zoo Welcomes Its First Baby of 2026: An Endangered Pileated Gibbon 19th February, 2026Conservation charity, Twycross Zoo, is celebrating a heart-warming milestone with the arrival of its first baby of 2026 - an endangered pileated gibbon,…

Twycross Zoo Welcomes Its First Baby of 2026: An Endangered Pileated Gibbon 19th February, 2026Conservation charity, Twycross Zoo, is celebrating a heart-warming milestone with the arrival of its first baby of 2026 - an endangered pileated gibbon,… -

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=c8eadb7dce959e1a8e6be51070cd0b3b) Conservation breeding success as Endangered spotted deer fawn is born at Bristol Zoo Project 19th February, 2026An extremely rare spotted deer fawn has been born at Bristol Zoo Project, marking another important conservation milestone for this Endangered species.…

Conservation breeding success as Endangered spotted deer fawn is born at Bristol Zoo Project 19th February, 2026An extremely rare spotted deer fawn has been born at Bristol Zoo Project, marking another important conservation milestone for this Endangered species.…

.png?w=100&h=50&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=172b661bdec369bc1ff96180325a93db)