Lizzy Humphries, Senior Keeper at Battersea Park Children's Zoo, writes about the role of zoos to educate on welfare portrayals on social media:

Cute and fluffy, snuggled up in blankets, dressed in children’s clothes, splashing in the bath, or juggling cat toys in someone’s flat. Pet otters have become a social media craze with #otter being viewed 4.1billion times on TikTok at the time of writing. Even though this is a generalised hashtag, it is difficult to find any footage showing wild otters when sifting through the top results.

The Asian short-clawed otter (Aonyx cinereus) population has declined by at least 30% in the last 30 years and this trend is expected to continue in the next 30 years (Wright et al., 2021). Much of this decline is due to poaching for the exotic pet trade, as more people fall in love with the cute animals they see on sites like TikTok.

Zoos are an essential part of the protection of the Asian short-clawed otter. Thanks to recent comprehensive research, globally, their genetic background is now much better known. However, with new evidence suggesting that social media fuels poaching, it is time for zoos to change tack. Zoos must approach the conservation of otters, and other animals affected by the exotic pet trade, by delving further into their own portrayal of human-animal interactions.

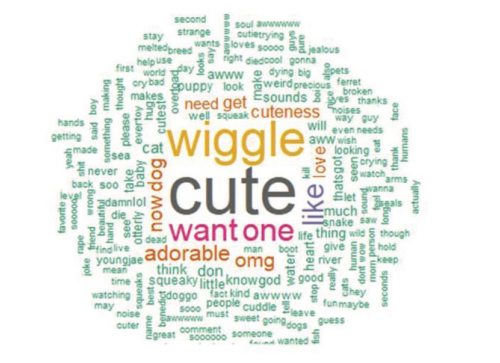

Conscious efforts have been made to change the way zoos portray their animals on social media, but it is difficult to prevent visitors from sharing footage that could be misinterpreted from their own social media accounts. When human-otter interaction is viewed on social media, it becomes normalised. The clicks and likes spread the image. When zoo social media accounts post uncontextualised pictures of an animal affected by the pet trade, they could accidentally encourage the trade, which can be seen when the posts receive public comments such as “I want one!”, “I just want to hug it!” The image of a keeper physically interacting with a wild animal normalises a behaviour which potentially has conservational repercussions.

Figure 1: Word cloud depicting the most commonly used words in the comment section of a 'pet otter influencer' video. The larger the word, the more frequently it was used (Harrington et al., 2019)

Asian short-clawed otters within the pet trade

A TRAFFIC report in 2018 found the primary threat to wild Asian short-clawed otters to be the illegal wildlife trade, recording over 900 individuals being advertised for the pet trade within 4 months.

An otter could be portrayed behaving like a domestic dog, an easy to handle animal (Harrington et al., 2019). People are therefore misled, meaning when they discover the truth about otters’ complex diet, habitat and social requirements and their extremely strong bite, pet otters are surrendered to rescues, or worse, dumped into the wild. It is common for juvenile pet otters to have their teeth and scent glands removed to make them ‘suitable’ pets (World Animal Protection, 2019).

While there is clear evidence that social media plays a negative role in the conservation of wild animals, it is still a relatively new area of interest with limited data. Zoos have an opportunity to change this. Many have an extensive reach on social media, and could use this to push messages promoting positive behavioural changes, as well as ensuring their own keepers’ behaviour does not accidentally confuse the message.

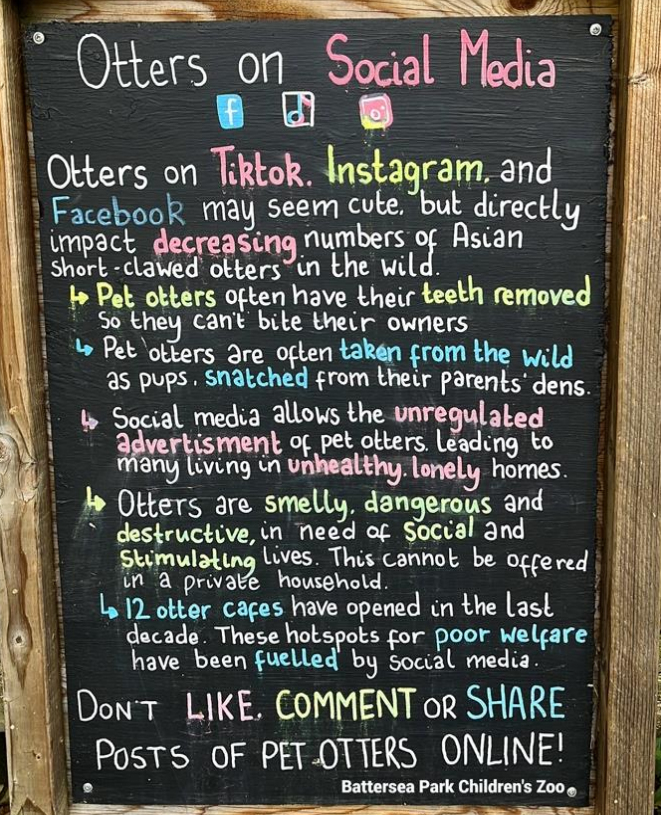

At Battersea Park Children’s Zoo, educating the public about the risks of poor social media usage is at the heart of both daily husbandry as well as educational and conservation work. Otters are strictly protected contact, so the public never sees keepers in close proximity with the them. The twice-daily talk has a heavy focus on the conservational problems caused by the exotic pet trade, as well as how to spot and react to inappropriate posts on social media. Signage is placed at the enclosure explaining these problems. The Zoo’s Instagram, Facebook and TikTok regularly post on the topic, and events are held by the education team on World Otter Day. The Zoo also works with the IUCN otter specialist group and the International Otter Survival Fund. The curator, Jason Palmer, is the WAZA, ISB and EAZA coordinator for Asian short-clawed otters, as well as an IUCN global species advisor.

Figure 2: Signage outside the otter enclosure at Battersea Park Children's Zoo

The responsibility of zoos to care for wild species is no longer limited to the husbandry that takes place within the confines of the collection. It is no longer enough to use social media to encourage people to visit the zoo, it must now be part of the conservational and educational armoury. Zoos have an extensive social media outreach, allowing them an opportunity to take charge of a resource which has the potential to both help and hinder conservation:

| What zoos can do | What keepers can do |

| Identify species whose conservational issues involve the exotic pet trade. Adapt husbandry accordingly; is it feasible to apply protected contact rules to these species? | Do NOT like, comment, share, or where possible, view, posts which feature wild animals being kept as pets. |

| Ensure that animal experiences do not offer an opportunity for the public to have photo opportunities that could be misconstrued. | Do not post photos on own social media accounts of close interaction with species whose wild counterparts are at high risk of poaching for the exotic pet trade. |

| Create a social media policy which ensures no photos are posted from the zoo account which show staff physically interacting with animals identified as being at high risk of misinterpretation. | Ensure own knowledge of the wild threats of the species within own care is up to date and make appropriate changes to behaviour based on this knowledge. |

| Create signage educating the public on how to navigate the exotic pet trade on social media. | Modify behaviour within enclosures to reduce the opportunity of photos being taken by the public which could be misconstrued. |

| Modify feeding time talks so that a conservational focus on the exotic pet trade flows throughout. | Start dialogue with friends and family about the risk of interacting with posts which may fuel the exotic pet trade. |

With a source of information as unregulated as social media, the only way of combatting its potential to play a part in the extinction of endangered species is to make it socially unacceptable to interact with posts that show wild animals being kept as pets. Zoos can start this change by adapting as organisations when considering enclosure design, signage, social media policy, education and husbandry.

There are opportunities to follow in the footsteps of global campaigns started by organisations such as the Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition (SMACC), to encourage the public to help the conservation of their favourite species (through not interacting with high risk posts on social media (SMACC, 2022). If all zoos committed to this dialogue, they could play a huge part in protecting animals such as Asian short-clawed otters through social and behavioural change in the hope that, in time, we will see a reversal in this modern, detrimental craze.

- Lizzy Humphries, Senior Keeper at Battersea Park Children’s Zoo

References

Gomez, L. and Bouhuys, J. (2018). Illegal otter trade in Southeast Asia. TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Harrington, L., Macdonald, D., & D'Cruze, N. (2019). Popularity of pet otters on YouTube: evidence of an emerging trade threat. Nature Conservation, 36, 17–45.

Okamoto, Y. (2022). Otter cafes: Pet trade in Japan and Asia. WWF

Social Media Animal Cruelty Coalition. (2022). Wild animal “pets” on social media: A vicious cycle of suffering. SMACC Spotlight report. https://drive.google.com/file/d/15RWT5HoaEEG9hFXAgihg2njZuDr3Eh5d/view?pli=1

World Animal Protection. (2019). Trending: Otters as exotic pets in Southeast Asia and the online activity fuelling their demise. World Animal Protection Canada. https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/sites/default/files/media/us_files/otters_as_exotic_pets_v6_singles.pdf

Wright, L., de Silva, P.K., Chan, B., Reza Lubis, I. & Basak, S. (2021). Aonyx cinereus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T44166A164580923. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T44166A164580923.en

All blogs reflect the views of their author and are not necessarily a reflection of BIAZA's positions.

Related Members

-

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=97e6d151315c515d23f80e6ee9d1d533) BIAZA Blog: How Accreditation is creating change at BIAZA 25th February, 2026After two years of BIAZA Accreditation, the team delivers a look ahead on the programme to support and boost world-class zoos…

BIAZA Blog: How Accreditation is creating change at BIAZA 25th February, 2026After two years of BIAZA Accreditation, the team delivers a look ahead on the programme to support and boost world-class zoos… -

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=a0b01e801771c24b4d7f5c3df4abed98) Twycross Zoo Welcomes Its First Baby of 2026: An Endangered Pileated Gibbon 19th February, 2026Conservation charity, Twycross Zoo, is celebrating a heart-warming milestone with the arrival of its first baby of 2026 - an endangered pileated gibbon,…

Twycross Zoo Welcomes Its First Baby of 2026: An Endangered Pileated Gibbon 19th February, 2026Conservation charity, Twycross Zoo, is celebrating a heart-warming milestone with the arrival of its first baby of 2026 - an endangered pileated gibbon,… -

News

.png?w=100&h=100&zc=1&f=jpeg&hash=c8eadb7dce959e1a8e6be51070cd0b3b) Conservation breeding success as Endangered spotted deer fawn is born at Bristol Zoo Project 19th February, 2026An extremely rare spotted deer fawn has been born at Bristol Zoo Project, marking another important conservation milestone for this Endangered species.…

Conservation breeding success as Endangered spotted deer fawn is born at Bristol Zoo Project 19th February, 2026An extremely rare spotted deer fawn has been born at Bristol Zoo Project, marking another important conservation milestone for this Endangered species.…